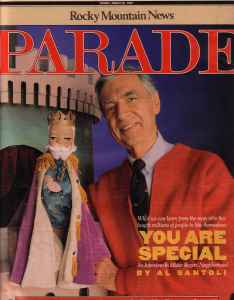

I Like You Just the Way You Are

Publication: Parade

Author: Al Santoli

Date: March 28, 1993

The best-known neighborhood in America cannot be found on a map. Each morning, millions of children use their imaginations to ride a red trolley to the home of their wise and thoughtful television neighbor, Mister Rogers. This season marks 25 years on the Public Broadcasting System that Fred Rogers has masterfully combined music, puppetry and relaxed conversation to explore our often turbulent world and inner feelings. In fact, Mister Rogers' Neighborhood is the longest-running program on public television. The bond of trust between Rogers and his "neighbors" is built on a comforting message to each child: "You are special, and I accept you just the way you are."

On a rainy morning in Pittsburgh, I visited Fred Rogers at the WQED television building in which Mister Rogers' Neighborhood is produced. We met in his office, one floor above the performing studio, where he writes many of the show's scripts and songs. Rogers' neatly combed hair is now mostly silver. At 65, he looked professional in a beige bow tie, navy-blue sport coat and dark-rimmed glasses. Off-camera, he speaks with the same warm and soft-spoken enthusiasm that is his broadcasting trademark. He proudly showed me photos of his 4-year-old grandson and asked about my own children. His eyes filled with tears when he described a small child who recently had died of cancer. "There is a universal truth I have found in my work," he said. "Everybody longs to be loved. And the greatest thing we can do is let somebody know that they are loved and capable of loving."

Although Rogers has been in television since its pioneering days, it was by chance that he became involved with children's programs. In 1951, he was a college senior preparing to attend a seminary when he first saw television at his parents' home in Latrobe, Pa. "I was appalled at a program with people throwing pies in each other's faces," he says. "I saw television as a real challenge. I wanted to make a difference."

He traveled to New York City with a degree in music and was hired as a production assistant at NBC. He worked on The Kate Smith Evening Hour, Your Hit Parade, Amahl and the Night Visitors and The Gabby Hayes Show, and he was floor manager for the first experimental color broadcasts. After two years -- and newly wed to his college classmate, Joanne Byrd -- Rogers returned to Pittsburgh to help start WQED, the nation's first publicly funded station.

"I kind of stumbled into doing a children's program," he recalls witha bemused chuckle. "There were only six people on the station's staff, and nobody wanted to do the program. So a secretary, Josie Carey, and I volunteered."

His show, The Children's Corner, lasted seven years, winning numerous awards. At the same time, Rogers gave up his lunch hours to attend seminary classes. "In seminary," he says, "I learned to find what is healthy and positive in people and somehow bring that to light to let it grow." And, while working on a counseling degree, he began collaborating with Dr. Margaret McFarland, a psychologist and director of the Arsenal Family and Children's Center, affiliated with the University of Pittsburgh. There he began to develop his Mister Rogers-style personality.

Mister Rogers' Neighborhood has changed little since it became nationally distributed in 1968. After Rogers sings "It's a beautiful day in the neighborhood" and changes into a comfortable sweater, he often talks or sings about experiences or emotions that all children face. The theme is then played out by puppets and costumed characters in "The Neighborood of Make Believe," before Mister Rogers returns to explain, slowly and carefully, how the puppets resolved the issue. In some segments, he introduces creative arts, like finger-painting or playing the harmonica.

"Creativity and imagination are the beginning of problem-solving for a child," he says. "Observing children's drawing, paintings and their use of toys can tell us much about the way they are feeling. Of course, some kids may try to use an imaginary friend to their advantage. They might blame their 'friend' as the one who did the mischief. If that happens, a parent should tell the child: 'Your friend is imaginary and couldn't possibly have done that. How about you helping me clean it up right now?'"

Rather than shying away from negative emotions like anger or jealousy, Rogers offers children positive alternatives to express how they feel. "The scariest thing for any child," he says, "is to feel out of control and that you don't have any choices." Constant themes of his songs are that somebody cares and that it's okay for a child to be a unique individual. This, he maintains, plants the fundamental seed of self-esteem as children grow older.

"Young children seem to learn best," he observes, "when they want to please somebody whom they love. As they grow, it's important that they are able to love the person who they are, so they will continue to want to learn and succeed in life. Parents are the best people to explain to children that there are no others in the world exactly like them. Parents can set the example by just being themselves, rather than trying to be perfect parents. Kids can detect phoniness a mile away.

"As a parent, I found it most helpful to remember the larger picture: That I really did love the kids. But there were times when I couldn't be with them. Or when I couldn't give them undivided attention. Both Joanne and I recall many times when we wish we had said or done something different. But we always cared and tried to do our best. Our two sons responded to that. I've realized that some things don't have to be perfect in order to be effective. And remember -- there is mystery in raising children: As your children grow and develop their unique talents, you can't control every aspect of their lives.

"Since I began doing my show in the '60s, the emotional development of children hasn't changed. But society encourages them to be exposed to adult themes at an early age. The introduction of drugs is one of the worst changes in society since I went on television. People with drug problems seem to have a lack of self-worth. The breakdown of the family is another problem. I would never have dreamed that we would produce a whole week of shows on divorce. We did that in as gentle a way as possible.

"Our main message was that divorce is a grown-up's problem. When tragic things happen in a family, preschool kids naturally believe it's because of them. It's important that they hear that it's not their fault. Whether children can assimilate the entire message or not, I don't think matters. At least they know that we adults are trying to help them make some kind of sense of what is going on in their world." And, he adds, always keep in mind that parents' love and personal examples constitute a more important influence than television.

Rogers' serene style of speaking, laced with meditative pauses, has been target of numerous satires. However, each program is purposely paced to resemble a dialogue between two friends. Three generations of children in America and many other countries have regularly visited the "Neighborhood" because they believe that Mister Rogers is a real person who cares about them.

After so many years of doing the program, Fred Rogers has no plans to slow down. "What keeps my work fresh," he says, "has always been my dedication to the children. That is reflected in the way that I look into the camera and let each child watching believe that I am talking directly to him or her. They're all my 'neighbors' -- and I'm theirs."